To: House Judiciary Committee

From: Christopher Dodson, Executive Director

Subject: HB 1498 - Use of Deadly Force

Date: February 15, 2021

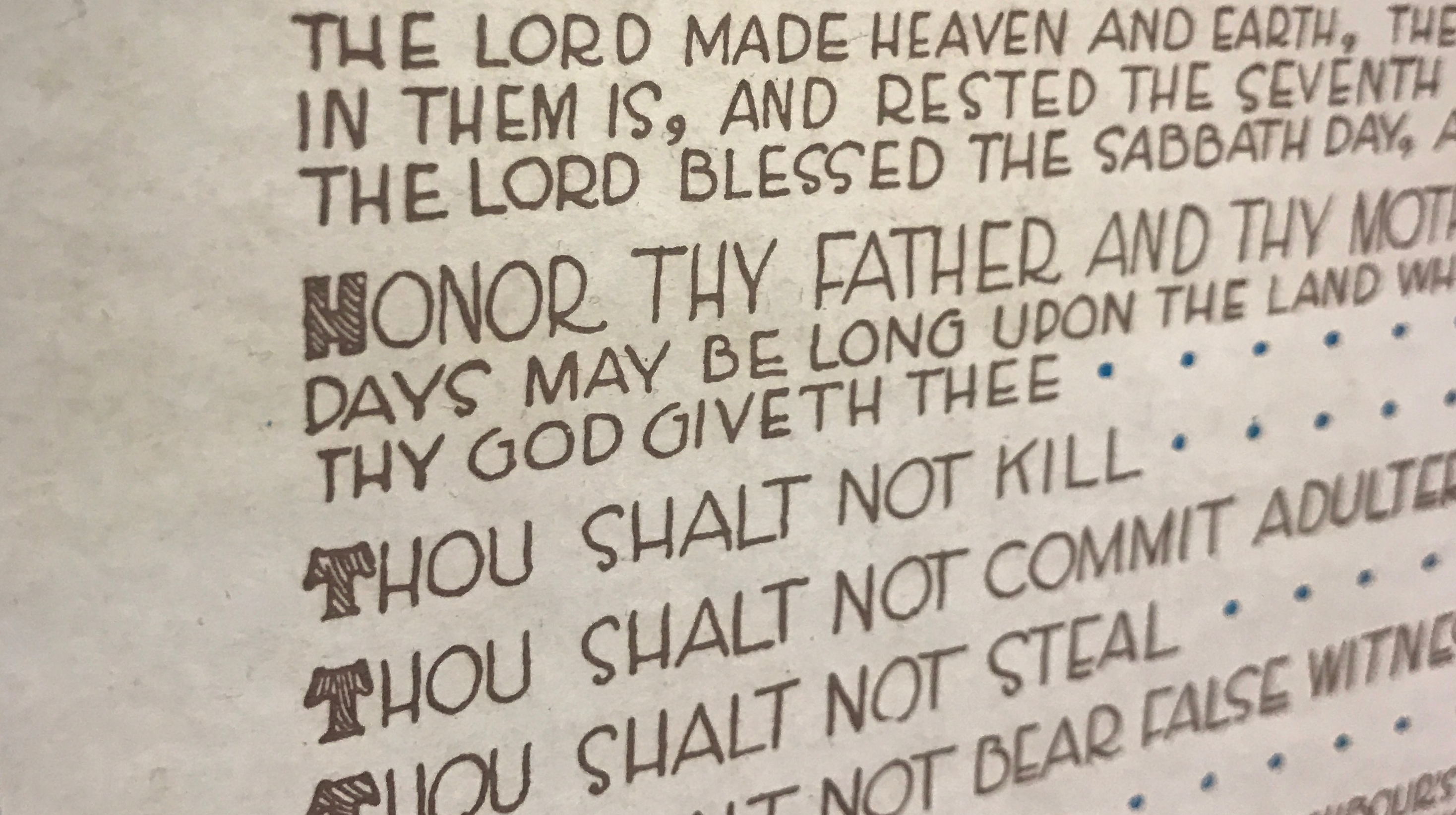

When and how much force an individual can use against another is ultimately a moral issue. The Bible presents the precept "You shall not kill" as a divine commandment. Those of different faiths or no faith accept the same injunction because they value of all human life. From this precept comes a fundamental principle: No one can claim the right to deliberately kill another human being. The injunction is rooted in the recognition that all human life is sacred and that all human life has inherent value.

Yet as far back as the Book of Exodus, faced with often tragic cases that can occur, we sought a fuller and deeper understanding of what the commandment prohibits and prescribes, particularly in cases of self-defense. Thomas Aquinas later provided the most accepted and definitive treatment of the subject. What he taught, though not entirely new even then, became the basis of Western Law.

Aquinas restated the fundamental principle that it is never permissible for a private individual to intentionally kill a person. This injunction applies even in cases of self-defense. A person can, however, use moderate force to repel an aggressor when it is necessary to protect oneself or someone for whom the person is responsible. If the use of force meets these conditions and the aggressor unintentionally dies as a result, the person is not guilty of murder. If however, these conditions are not met and the aggressor dies, the person has committed murder.

Three fundamental principles underlie this teaching. First, intentional killing of an innocent person is always wrong. Second, intentional killing of a wrongdoer is also always wrong, though the use of force that unintentionally results in the death of a wrongdoer can be justified. Third, the mere fact that an individual is not where he or she should be or may be intending harm does not create an exception to the rule. Even in that case, a person cannot intend to kill the individual.

Through the centuries, courts and lawmakers incorporated these principles into law. The “duty to retreat” in English common law finds its basis in the necessity requirement, since the use of deadly force could not be viewed as necessary if the person could escape. Eventually, some jurisdictions, including North Dakota, adopted the “Castle Doctrine,” which removed the duty to retreat in a person’s dwelling or work place. The Castle Doctrine does not necessarily contradict the fundamental principles since it is based on several presumptions about the ability to retreat.(1)

House Bill 1498 contradicts these fundamental moral principles. The bill’s removal of the requirement to avoid the use of deadly force by retreat or other conduct when safely possible would, practically by definition, allow intentional killing when it is not necessary. This violates the fundamental moral rule that a person cannot use deadly force except when it is necessary for self-defense.

The iteration of this bill appears to keep the duty to retreat while merely changing the circumstances in which Castle Doctrine applies. In truth, however, the bill essentially eliminates the Castle Doctrine and replaces it with an exception that swallows the rule.

The new language removes the Castle Doctrine and replaces it with an “everywhere” doctrine. The only limitation is that person must not be engaged in unlawful activity and must be where they are allowed to be. Essentially, it says that “good guys” can use deadly force and that “bad guys” cannot. The enforcement problem with this is that, legally, there are no good guys or bad guys until it has been determined by law.

A more fundamental problem, however, is that negates the basic moral principles stated above. Intentionally killing a wrongdoer is also always wrong. The mere fact that an individual is not where he or she should be or may be intending harm does not create an exception to the rule. HB 1498 essentially eliminates the duty to retreat in situations other than dwellings and work and, therefore, would allow the use of deadly force when it is not needed for self-defense.

We urge a Do Not Pass recommendation.

(1) Indeed, something like the Castle Doctrine appears in Exodus 22:1. It states: “If a thief is caught in the act of housebreaking and beaten to death, there is no bloodguilt involved.” The next verse, however, states: “But if after sunrise he is thus beaten, there is bloodguilt.” In other words, killing an intruder at night was permissible because escape was presumed not possible in the dark, but killing in an intruder during the day was not acceptable because escaping was possible in daylight.

From: Christopher Dodson, Executive Director

Subject: HB 1498 - Use of Deadly Force

Date: February 15, 2021

When and how much force an individual can use against another is ultimately a moral issue. The Bible presents the precept "You shall not kill" as a divine commandment. Those of different faiths or no faith accept the same injunction because they value of all human life. From this precept comes a fundamental principle: No one can claim the right to deliberately kill another human being. The injunction is rooted in the recognition that all human life is sacred and that all human life has inherent value.

Yet as far back as the Book of Exodus, faced with often tragic cases that can occur, we sought a fuller and deeper understanding of what the commandment prohibits and prescribes, particularly in cases of self-defense. Thomas Aquinas later provided the most accepted and definitive treatment of the subject. What he taught, though not entirely new even then, became the basis of Western Law.

Aquinas restated the fundamental principle that it is never permissible for a private individual to intentionally kill a person. This injunction applies even in cases of self-defense. A person can, however, use moderate force to repel an aggressor when it is necessary to protect oneself or someone for whom the person is responsible. If the use of force meets these conditions and the aggressor unintentionally dies as a result, the person is not guilty of murder. If however, these conditions are not met and the aggressor dies, the person has committed murder.

Three fundamental principles underlie this teaching. First, intentional killing of an innocent person is always wrong. Second, intentional killing of a wrongdoer is also always wrong, though the use of force that unintentionally results in the death of a wrongdoer can be justified. Third, the mere fact that an individual is not where he or she should be or may be intending harm does not create an exception to the rule. Even in that case, a person cannot intend to kill the individual.

Through the centuries, courts and lawmakers incorporated these principles into law. The “duty to retreat” in English common law finds its basis in the necessity requirement, since the use of deadly force could not be viewed as necessary if the person could escape. Eventually, some jurisdictions, including North Dakota, adopted the “Castle Doctrine,” which removed the duty to retreat in a person’s dwelling or work place. The Castle Doctrine does not necessarily contradict the fundamental principles since it is based on several presumptions about the ability to retreat.(1)

House Bill 1498 contradicts these fundamental moral principles. The bill’s removal of the requirement to avoid the use of deadly force by retreat or other conduct when safely possible would, practically by definition, allow intentional killing when it is not necessary. This violates the fundamental moral rule that a person cannot use deadly force except when it is necessary for self-defense.

The iteration of this bill appears to keep the duty to retreat while merely changing the circumstances in which Castle Doctrine applies. In truth, however, the bill essentially eliminates the Castle Doctrine and replaces it with an exception that swallows the rule.

The new language removes the Castle Doctrine and replaces it with an “everywhere” doctrine. The only limitation is that person must not be engaged in unlawful activity and must be where they are allowed to be. Essentially, it says that “good guys” can use deadly force and that “bad guys” cannot. The enforcement problem with this is that, legally, there are no good guys or bad guys until it has been determined by law.

A more fundamental problem, however, is that negates the basic moral principles stated above. Intentionally killing a wrongdoer is also always wrong. The mere fact that an individual is not where he or she should be or may be intending harm does not create an exception to the rule. HB 1498 essentially eliminates the duty to retreat in situations other than dwellings and work and, therefore, would allow the use of deadly force when it is not needed for self-defense.

We urge a Do Not Pass recommendation.

(1) Indeed, something like the Castle Doctrine appears in Exodus 22:1. It states: “If a thief is caught in the act of housebreaking and beaten to death, there is no bloodguilt involved.” The next verse, however, states: “But if after sunrise he is thus beaten, there is bloodguilt.” In other words, killing an intruder at night was permissible because escape was presumed not possible in the dark, but killing in an intruder during the day was not acceptable because escaping was possible in daylight.

What We Do

The North Dakota Catholic Conference acts on behalf of the Roman Catholic bishops of North Dakota to respond to public policy issues of concern to the Catholic Church and to educate Catholics and the general public about Catholic social doctrine.

Contact Us

North Dakota Catholic Conference

103 South Third Street, Suite 10

Bismarck, North Dakota

58501

1-888-419-1237

701-223-2519

Contact Us